Yoshua Okón Con Tony Labat

¿Qué estás haciendo?

Estoy trabajando en una pieza nueva. Grabé un video en el pueblo de Skowhegan, en Maine. Durante el verano fui profesor residente en una escuela que está junto al pueblo.

Me comentan que eres muy popular actualmente, ¿es cierto?

¡No sé! ¿Quién te dijo eso?

Eso es lo que me dicen, que eres muy popular. Esto es fantástico, es un placer conversar contigo. Estaba pensando en cómo, por un lado, conozco mucho sobre tu trabajo, y por otro, sé muy poco sobre ti. Entonces, el comienzo sería algo como ¿en dónde creciste y cómo fueron los primeros años de tu vida?

Bueno, nací en 1970 y crecí en la Ciudad de México. De hecho, es el mismo vecindario en donde vivo todavía. Crecí en la Condesa, así es que no me he movido mucho.

¿Y fuiste a UCLA?

Sí, hice mi maestría en Artes Visuales en UCLA

Comencemos con un poco acerca de La Panadería. ¿Cómo surgió?

En realidad, esto regresa a mi infancia y a mi crianza. Definitivamente está conectado. Durante los setenta y en especial en los ochenta, cuando estaba creciendo, México difícilmente participaba en la escena internacional. Había un proteccionismo económico muy fuerte y un régimen totalitario, por lo que era muy difícil tener acceso a la cultura del extranjero. También era muy difícil tener acceso a los artistas e intelectuales interesantes que trabajaban en la misma ciudad, ya que había un poderoso monopolio de los medios (que no ha cambiado mucho), y eran tiempos previos al Internet. Los museos públicos solamente exhibían arte abstracto que no amenazaba al régimen de ninguna manera. Entonces, crecí aquí y estaba hambriento de información. Sabía que quería ser artista, pero me sentía aislado, por lo que en 1989 me fui a estudiar al extranjero. Me fui a Montreal, en donde había muchos espacios gestionados por artistas y, junto a Miguel Calderón; que al mismo tiempo vivía en San Francisco, qué también es una ciudad con una larga tradición de espacios independientes gestionados por artistas; comenzamos a imaginar la forma de cambiar las cosas en casa. Creo que ese es el ímpetu inicial para La Panadería. En otras palabras, queríamos expandir las posibilidades de la vida diaria en la Ciudad de México. Queríamos abrir las cosas y también estábamos muy interesados en crear un puente con el exterior. Queríamos traer artistas interesantes y viajar al extranjero para entrar en un dialogo más amplio, para reconectar internacionalmente a la Ciudad de México. Porque durante el periodo modernista la ciudad fue muy cosmopolita y culturalmente compleja, hasta finales de los 60; cuando sucedió la masacre estudiantil y, con la conformidad de la CIA, el régimen se hizo sumamente represivo. Entonces, cuando La Panadería abrió, establecimos un espacio de residencia para nuestros invitados, y también comenzamos a invitar a gente de los alrededores de la ciudad que necesitaban un lugar para exhibir y para interactuar. Desde ahí, las cosas se desarrollaron de una forma muy orgánica.

Creo que mencionaste algo con lo que me gustaría continuar un poco. Cuando fuiste a Canadá, y luego también a San Francisco, los espacios gestionados por artistas eran, bueno, de cierta manera estaban llegando a la cúspide. Entonces ¿consideraste esos espacios como modelo?

Sí, quiero decir, no eran el único modelo, pero la tradición de espacios gestionados por artistas definitivamente se convirtió en un modelo; ese tipo de iniciativas artísticas no gubernamentales y no corporativas.

Pero al mismo tiempo, para mí, la diferencia es—y corrígeme si me equivoco—que solamente eran ustedes dos. No tenían un consejo, ni asesores ni nada similar, ¿correcto?

Es correcto. Pero más allá de estructuras particulares, lo que nos influenció fue el espíritu de juntarse y abrir tu propio espacio en tu cochera para tener toda la libertad posible. Entonces, adaptamos este espíritu a nuestro propio contexto e inventamos una estructura que tenía sentido para el tiempo y espacio específicos. Y un elemento clave fue mi padre. Él formó parte del movimiento estudiantil y es un anarquista en espíritu, y apoya mucho a las artes. Así que él es quien, de manera gratuita, nos prestó el lugar en donde todo sucedió. Y como no lo estábamos haciendo por el dinero, no era necesario constituir un consejo para que este espacio sucediera. Era una plataforma que pertenecía a los artistas, por lo que fue la multiplicidad de los artistas lo que determinó lo que sucedió ahí.

¿A qué te refieres con que tu padre era un anarquista?

Mi padre estudio con los anarquistas republicanos que eran refugiados políticos de la Guerra Civil Española aquí en México. Intelectuales humanistas increíbles, que abrieron muchas escuelas y tuvieron una influencia cultural muy positiva (entre ellos, Luis Buñuel). También fue parte del movimiento estudiantil de 1968 aquí en la Ciudad de México. Pertenece a la generación desencantada de activistas progresivos de los sesenta, que fue prácticamente deshecha a finales de esa década y en los setenta. Entonces, en muchos niveles simpatizaba con La Panadería. Se convirtió en mecenas y, con su apoyo y la estructura que se nos ocurrió, en la que los artistas cubrían su propia producción y el dinero de la venta de cerveza en las inauguraciones cubría los costos básicos, el espacio duró nueve años. Definitivamente encontramos un balance y un pequeño sistema que funcionaba. Otro aspecto importante era que, de alguna manera, el gobierno se dio cuenta de que estaba sucediendo algo culturalmente significativo, y no sólo nos permitieron operar sin estar constituidos legalmente, sino que, incluso, nos protegían. Cuando recuerdo las cosas tan locas que hicimos, me doy cuenta de cuanta tolerancia había por parte del gobierno de la ciudad. Y no es una coincidencia, ya que eran los días en los que Cuauhtémoc Cárdenas, un político muy progresista y respetado, se convirtió en gobernador de la ciudad, reemplazando el increíblemente corrupto partido (PRI) que había estado gobernando la ciudad por casi 70 años. Ahora, el PRD, el partido de Cárdenas, aún gobierna la ciudad, aunque desafortunadamente se está haciendo más corrupto. Pero esa es otra historia.

Definitivamente ayudaste a poner a la Ciudad de México en el mapa.

Para bien o para mal.

Creo que para bien. Obviamente eres un artista que está interesado en la producción de cultura y, quizás de cierto modo, en activismo. Como mencionabas, eso te llevó recientemente—no sé cuántos años lo has estado haciendo—pero tienes esta escuela. ¿Podrías contarme un poco acerca de esa transición de gestionar un espacio de artistas a gestionar una escuela?

Claro. Bueno, SOMA también es un espacio independiente, sin ánimo de lucro, dirigido por artistas. Proviene de la misma tradición que La Panadería. Pero el contexto en el que existe SOMA es muy diferente al que encontramos en los noventa. A principios de los noventa, el mercado no jugaba ningún papel. Había muy pocos espacios exhibiendo arte contemporáneo. Ahora hay muchos espacios de exposición. Eso es lo último que necesitamos. En el fondo, la misión no ha cambiado mucho, pero SOMA está respondiendo a un nuevo paradigma cultural y, por lo tanto, necesita nuevas estrategias. Los programas de SOMA están diseñados para ser un contrapeso de las tendencias culturales neoliberales que predominan hoy en día, así como para estimular el intercambio intergeneracional. Los tres programas principales son: Miércoles de SOMA, un programa abierto al público y gratuito en donde cada miércoles invitamos a alguien para hablar o presentarse. Este es un programa multidisciplinario. A veces tenemos urbanistas o filósofos, otras veces son artistas, a veces músicos. Se trata de conocer lo que está pasando, una forma en que los agentes culturales pueden hablar a profundidad sobre su práctica y un modo de estimular más diálogo y más interacción entre los actores culturales en la ciudad. Otro es un programa a nivel de posgrado con duración de dos años y con 24 estudiantes. Finalmente, hay un tercer programa que es una residencia de verano de ocho semanas, en inglés. Esos son los tres programas actuales en SOMA, pero podrían cambiar en el futuro. Yo no me refiero a SOMA como una escuela. Me refiero a éste como un espacio de artistas con un consejo que se encarga de determinar el contenido y hacia dónde se mueven las cosas.

An individual critique with Paola Santoscoy and Kristin Reger (from the SOMA Summer Program). Courtesy of SOMA.

¿Cuál es tu papel en SOMA?

Bueno, yo lo fundé, y actualmente soy parte del consejo de artistas. Hay una directora, Bárbara Hernández, que esta haciendo un traba- jo estupendo. Ella opera el día a día y tiene formación como gestora cultural. Tiene un equipo y ella no define el contenido, pero se asegura de que las ideas y el programa que vienen del consejo de artistas se haga realidad.

¿Podrías decirme algo sobre los artistas que están involucrados contigo en el consejo?

Claro. Somos 19. Algunos de ellos son Teresa Margolles, Santiago Sierra, Francis Alÿs, Carlos Amorales, Julieta Aranda, Eduardo Abaroa y Sofía Táboas. Todos contribuimos de distintas maneras, dependiendo de nuestras habilidades, disponibilidad e intereses. Algunos enseñan, otros programan las charlas de los miércoles, otros nominan estudiantes, otros invitan residentes, otros están involucrados conceptualmente en la forma en la que todo el espacio se mueve y se desarrolla, etc. Los prerrequisitos para los miembros son que cuenten con una fuerte conexión con la Ciudad de México y una práctica madura e internacionalmente activa.

Suena muy bien. ¿Por cuánto tiempo has estado hacien- do esto?

La inauguración fue en noviembre de 2009. Así que durante casi cinco años.

Increíble. Ahora bien, ¿qué hay de ti? Mencionaste que estás trabajando en un nuevo video. ¿Podrías contarme un poco sobre eso?

Claro. Desde el principio, mi práctica ha tenido un énfasis social muy fuerte. Eso no quiere decir que no me interesan las cuestiones formales, pero no son dos categorías que se excluyan mutuamente; la forma sin discurso es algo que nunca me ha interesado. Sin embargo, no es activismo, pues creo que el activismo es una cosa diferente. Mi trabajo opera sobre una base social y habla sobre aspectos de interés común que tenemos como sociedad. La práctica que he desarrollado, en términos generales, es un híbrido entre el performance, el video y la instalación. Usualmente comienzo con investigación entorno a sitios específicos, comunidades, o hechos históricos, y desde ahí incorporo la ficción. En el montaje final, es importante la relación del video con el espacio y con el cuerpo. Estoy interesado en las áreas grises entre la ficción y el documental porque, al hacerlas aparentes, los espectadores tienden a interpretar activamente lo que están mirando y, por lo tanto, a formular su propia interpretación de la realidad. Y esta formulación personal de significado es lo que considero que es la principal diferencia entre lo que hago y el activismo, en el que siempre hay una agenda.

El pueblo en el que grabé el proyecto que actualmente estoy editando está en medio de un área rural muy pobre en Maine. Mientras estaba ahí, estaban restaurando una enorme escultura que la Cámara de Comercio del pueblo construyó en los sesenta. Es una escultura de madera de unos 80 pies de un nativo americano al que se refieren como “el indio más alto del mundo.” Investigando un poco encontré que el nombre original del pueblo se había cambiado por un nombre nativo americano y, años después, construyeron la estatua en un esfuerzo por atraer al turismo. Y también encontré que algunos de los peores genocidios de nativos americanos en Estados Unidos sucedieron precisamente en esa parte del país, en Nueva Inglaterra. Entonces, fue algo así como ¿por qué esta estatua de un nativo americano? ¿Hay nativos americanos en los alrededores? Resulta que no, no hay ninguno viviendo en Skowhegan. Sé que es una práctica común en Estados Unidos apropiarse y exotizar culturas nativo americanas, y que es una práctica que se ha normalizado hasta el punto en que es difícil verlo, pero para mí, viniendo del exterior, es una locura. Es decir, es como si los nazis hubieran ganado la guerra y luego decidieran usar un rabino como la mascota de una ciudad en Alemania sin ningún reconocimiento del genocidio, ¿sabes?

¿Entonces la renombraron porque sonaba indio?

Exactamente.

¿Y qué significa Skowhegan?

Significa el lugar en donde se buscan peces. Cruzando Skowhegan hay un río enorme llamado Kennebec, en donde los nativos americanos solían pescar. Para mi pieza, le pedí a los miembros del comité del pueblo que estaban encargados de la restauración que hablaran en un panel de discusión en la estación local de televisión acerca de la historia de la escultura y sobre el uso de los nativos americanos como símbolo de su identidad. Bajo mi dirección, el panel de discusión se transformó lentamente en un extraño “trance ceremonial nativo americano” que sucedió por toda la estación de televisión. Esta segunda parte la dejé bastante abierta a su interpretación. Entonces sí, eso es básicamente lo que estoy editando ahora. La pieza final será una instalación de tres canales.

¿Cuánto tiempo estuviste ahí?

Estuve ahí durante nueve semanas. Fue muy bueno porque estaba dando clases pero también tuve el tiempo para hacer la investigación y grabar durante mi última semana.

Entonces en eso estás trabajando ahora, ¿estás editando la pieza?

Estoy editando esa pieza y también me estoy preparando para una exposición individual en noviembre en la galería Kake, en Okayama. Japón. Y pronto comenzaré una nueva producción para una exposición en un espacio llamado HOME, en Manchester, Inglaterra, que ellos están produciendo. Y finalmente, estoy trabajando en el Museo de Arte de Phoenix, en Arizona.

¿Estás trabajando con Julio César Morales?

Con Julio…

Yo a Julio lo llamo “mayonesa”. Por escurridizo. ¿Cuándo es la exposición en Arizona?

Bueno, siempre había querido hacer una pieza sobre los Minutemen en Arizona. Cuando Julio empezó a trabajar ahí, me preguntó sobre la posibilidad de trabajar juntos y le conté sobre la idea de los Minutemen. Tomó un poco más de un año, pero finalmente me organizó entrevistas con gente por todo el estado. Así que lo haremos en tres etapas. Primero será la investigación de campo en noviembre, luego la producción y al final la exhibición, para la que no hemos puesto fecha todavía.

No quiero cambiar tanto el tema pero, ¿cuál es tu opinión sobre la forma en que la Ciudad de México se encaja en la escena actual del arte contemporáneo mundial en cuestiones como las ferias y Zona Maco? ¿Cuál es tu opinión sobre lo que está sucediendo en la Ciudad de México hoy? Hablaste un poco sobre los sesenta, los setenta y hasta los ochenta, y después algo de los noventa con La Panadería, y ahora mencionas un poco la forma en que las cosas han cambiado, pero ¿en dónde lo ubicas hoy y cómo lo ves?

El mundo del arte aquí está sumamente globalizado. México se incorporó al circuito internacional del arte y, como en muchos otros lugares, hay cada vez más agentes que provienen de sectores no culturales, como los negocios y las finanzas. Entonces, eso significa que la escena del arte en el D.F. ha crecido mucho, pero que en general el énfasis se ha volteado hacia el espectáculo y el lucro y se ha alejado de la cultura. Zona Maco es un buen ejemplo de eso. Pero al mismo tiempo, la escena del arte es compleja y hay muchas otras fuerzas en juego que operan con una lógica diferente. Hay mucho museos y galerías públicos en la ciudad con un muy buen nivel, hay un simposio internacional de arte una vez al año (SITAC), nuevas publicaciones, y una población grande de artistas que cada vez abren más espacios y hacen proyectos. Entonces, la escena en la Ciudad de México es bastante compleja.

¿Cómo describirías la palabra “espectáculo”?

Espectáculo significa que todo está sobre la superficie.

¿Entonces son objetos grandes y brillantes?

Objetos grandes y brillantes, o eventos que se tratan más sobre agendas corporativas o millonarios especulando en el mercado, que sobre cualquier tipo de contenido.

Cuando hablas en un nivel internacional/global, ¿significa que son artistas extranjeros que vienen y exponen o es principalmente una escena de artistas mexicanos?

No, significa que las escenas del arte en centros culturales como la Ciudad de México no pueden entenderse dentro de un paradigma de estado-nación. Los artistas en los museos o galerías pueden ser de cualquier lado, así como los curadores, coleccionistas, etc. Es muy internacional.

Entonces, hoy La Panadería estaría perdida –si regresamos el tiempo y decimos que quieres hacer un espacio gestionado por artistas en la Ciudad de México hoy, ¿sería posible?

Bueno, eso es SOMA. De muchas formas, SOMA es La Panadería reinventada y adaptada a este paradigma cultural tan diferente que acabo de describir. SOMA intenta ser el contrapeso al poner el énfasis en el contenido y el discurso, y por darle poder a los artistas para que podamos ejercer nuestra agencia. Por ejemplo, si hay una exposición interesante en la ciudad, invitamos al artista a dar una charla en SOMA y hablar a profundidad sobre su trabajo. SOMA es una plataforma en donde se pueden dar conversaciones, y donde el contenido que tratan los artistas tiene un eco.

Exactamente. ¿Cuál es el perfil de tus estudiantes? ¿Son todos mexicanos o vienen de todos lados?

De hecho, de todos lados. Eso es algo que anticipamos para el programa de verano en inglés, pero no para el programa de dos años en español. Pero resulta que hay una demanda internacional para lo que SOMA ofrece, porque tenemos estudiantes de Colombia, Francia, España, Italia, Brasil, Estados Unidos, y también estudiantes de todo México.

Hay una última cosa que quiero –no sé si quieres hablar de eso o no, pero todavía recuerdo cuando yo iba a hacer una exhibición en La Panadería y a ti te secuestraron.

Y la gente pensó que habías sido tú.

Todos me culparon. Y todavía recuerdo cuando Carlo McCormick me llamó y me dijo “amigo, esto es algo que ya habías hecho, ¿por qué sigues haciendo está pieza?” ¡Y traté de convencerlo de que yo no lo había hecho! Creo que fue la mejor pieza que he hecho. Me quedo con todo el crédito. Bueno, Yoshua, ha sido realmente un placer.

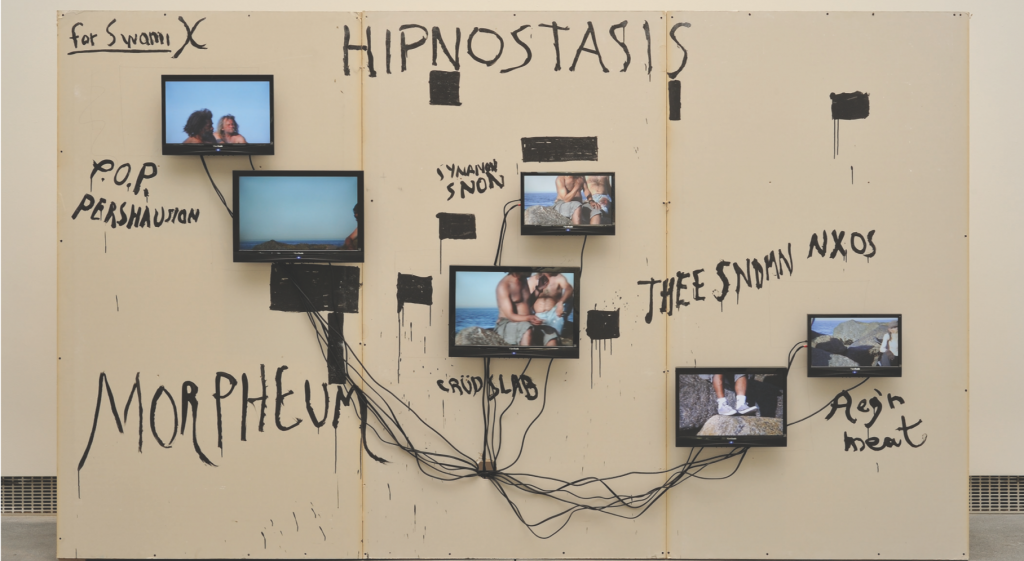

Hipnostasis, 2009. In collaboration with Raymond Pettibon. Installation view. YBCA, San Francisco. Courtesy of the artist.

![Risas Enlatadas [Canned Laughter], 2009. Installation view, Via Farini, Milan, Italy. Courtesy of the artist.](http://dfaq.mx/wp-content/uploads/2014/11/Screen-Shot-2014-11-17-at-10.51.07-1024x607.png)

Risas Enlatadas [Canned Laughter], 2009. Installation view, Via Farini, Milan, Italy. Courtesy of the artist.

———

Yoshua Okón With Tony Labat

What are you working on?

I am working on a new piece I shot in the town of Skowhegan in Maine during the summer. I was resident faculty at an art residency right next to the town.

They tell me that you are very hot right now, is that true?

I don’t know! Who said that?

That’s what they tell me, that you’re very hot. Hey, so this is fantastic, it is my pleasure to be talking with you. Okay, so listen, I was thinking about how in one way I know a lot about your work, and in another way I know very little about you. So maybe something to start with would be asking where you grew up and what your early life was like.

Okay, well I was born in 1970 and I grew up in Mexico City. Actually in the same neighborhood where I still live. I grew up in Condesa, so I haven’t moved much.

And you went to UCLA?

Yes, I did my MFA at UCLA.

Let’s start with a little bit about La Panadería. How did that come about?

This actually does go back to my childhood and my upbringing. It is definitely connected. Mexico during the 1970s and especially the 1980s when I grew up was hardly participating in the international scene. There was very strong economic protectionism and a totalitarian regime, so it was very hard to have access to culture from abroad. It was also very hard to have access to interesting artists and intellectuals working in your own city since there was a powerful media monopoly (that hasn’t changed all that much) and these were pre-Internet days. Public museums were only showing abstract art that didn’t threaten the regime in any way. So I grew up here and I was hungry for information. I knew I wanted to be an artist, but I felt quite isolated, so in 1989 I went to study abroad. I went to Montreal, where they had a lot of artist-run spaces, and together with Miguel Calderón, who simultaneously was living in San Francisco, also a city with a long tradition of independent artist-run spaces, we began trying to imagine how to make things different at home. I think that was the basic initial impetus for La Panadería. In other words, we wanted to expand possibilities in day-to-day life here in Mexico City. We wanted to open things up, and we were also very interested in creating a bridge with the outside. We wanted to bring interesting art- ists and travel abroad to enter into a broader dialogue, to re-connect Mexico City internationally. Because this was a very cosmopolitan and culturally complex city during the modernist period, up until the late ‘60s when the student massacre took place, and with the compliance of the CIA, the regime became highly repressive. So when La Panadería opened we set up a residency space for our guests and we also started to invite people from around the city that needed a place to show and needed a place to interact. In a very organic way things just took off from there.

You mentioned something that I would like to follow up on a little bit. When you went to Canada, and then San Francisco as well, the artist-run spaces were very—well, they were peaking—so you looked at those spaces as a model?

I mean, yes, they were not the only model, but the tradition of art- ist-run spaces definitely became a model; these kinds of non-governmental and non-corporate artist initiatives.

But at the same time, the difference is, for me, and correct me if I’m wrong, that it was just the two of you. You didn’t have a board or advisers or anything like that, correct? That’s correct. But beyond the particular structures, it was the spirit of getting together and opening your own space in your garage to have as much freedom as possible that influenced us. So we adapted this spirit to our own context and invented a structure that made sense for the specific place and time. And a key element was my father. He was part of the student movement and in spirit he’s an anarchist and is very supportive of the arts. So he is the one that, for free, lent us the building where everything took place. And since we were not doing it for money, it wasn’t necessary to establish a board to make this place happen. It was a platform that belonged to artists, so it was the multiplicity of artists that determined what took place there.

What do you mean your father was an anarchist?

My father studied under Republican anarchists that were political refugees here in Mexico from the Spanish Civil War. They were incredible humanist intellectuals that opened many schools and had a hugely positive cultural influence (Luis Buñuel among them). And he was also part of the 1968 student movement here in Mexico City. He belongs to the 1960s disenchanted generation of progressive activists that was pretty much crushed during the late sixties and seven- ties. So on many levels he sympathized with La Panadería. He became a patron, and with his support and the structure that we came up with in which artists covered their own production and the money from selling beer at the openings covered basic costs, the space lasted nine years. We definitely found a balance and a little system that worked. Another important aspect was that somehow the government realized something culturally significant was going on and not only did they allow us to operate with no legal status but we were even protected. When I look back at the crazy things we did, I realize how much tolerance there was from the city’s government. And it is not a coincidence since those were the days in which Cuauhtémoc Cárdenas, a very progressive and well-respected politician, became the mayor of the city replacing the incredibly corrupt party (PRI) that had been governing the city for almost 70 years. Now the PRD, Cárdenas’s party, still governs the city but unfortunately is becoming increasingly corrupt. But that is a different story.

Well you definitely were part of putting Mexico City on the map, that’s for sure.

For better or for worse.

I think for better. Okay, so obviously you are an artist who is interested in the production of a culture, and perhaps in a certain way, activism. Like you were saying, and that led you to recently—I don’t know how many years you’ve been doing it, but you have this school. Can you tell me a little bit about that transition? From running an artists’ space to running a school?

Sure. Well, SOMA is also an independent, non-profit, artist-run space. It comes from the same tradition as La Panadería. But the context in which SOMA exists is incredibly different from the one that we found in the 1990s. In the early 1990s, the market did not play a role at all. There were very few places exhibiting contemporary art. Now there are many exhibition places. That’s the last thing we need. Deep down the mission has not changed all that much but SOMA is responding to a new cultural paradigm and therefore needs new strategies. SOMA’s programs are designed to counterbalance today’s predominant neo-liberal cultural tendencies as well as to stimulate intergenerational exchange. The main three programs are: Miércoles de SOMA, a multidisciplinary program, free and open to the public, in which every Wednesday we invite someone to either talk or perform. So sometimes we have urbanists or philosophers, sometimes artists, sometimes musicians. It is about learning what is going on, a way for cultural agents to talk in depth about their practice and a way of stimulating more dialogue and more interaction among the cultural players in the city. Another is a two-year postgraduate level program with 24 students. And then finally there is a third program that is an eight-week summer residency in English. Those are the three current programs at SOMA, but they could change in the future. I don’t refer to SOMA as a school. I refer to it as an artist-run space with an artist council that’s in charge of determining the content and where things move.

Coyotería, 2003. Performance view. Mexico City. Courtesy of the artist. What is your role at SOMA?

Well, I founded it, and right now I am part of the artist council. There is a director, Barbara Hernandez, who is doing a fantastic job. She operates the day to day and is trained as an art administrator. She has a team, and she doesn’t define the content, but she makes sure that the ideas and programming that come from the artist council become a reality.

Can you tell me who are some of the artists involved in the council with you?

Sure. There are 19 of us. Among these are Teresa Margolles, Santiago Sierra, Francis Alÿs, Carlos Amorales, Julieta Aranda, Eduardo Abaroa and Sofia Taboas. We all contribute in different ways depending on our abilities, availability and interests. Some teach, others program the talks on Wednesday, others nominate students, others invite residents, others are conceptually involved in the way the whole space is moving and developing, etc. The prerequisites for the members are a strong connection to Mexico City and an active and mature art practice.

It sounds amazing. How long have you been doing this now?

The opening was in November 2009. So almost five years now.

Incredible. Listen, how about you now? You mentioned that you are working on a new video. Can you tell me a little bit about that?

Sure. Since the very beginning my practice has had a very strong social emphasis. And that is not to say that formal issues don’t interest me, but these two are not mutually exclusive categories; form without discourse is something that has never interested me. However, it is not activism, because I think activism is a different thing. My work operates in a social arena and it addresses aspects of the common ground we have as a society. The practice I have developed, roughly speaking, is a hybrid of performance, video, and installation. I usually begin with research based around specific sites, communities, or historical facts, and from there I incorporate fiction. In the final installation, the relationship of video to space and to the body is important. I am interested in the gray areas between fiction and documentary because in making these apparent, viewers tend to actively interpret what they are watching and therefore formulate their own personal interpretation of reality. And this personal formulation of meaning is what I consider to be the main difference between what I do and activism, where there is always an agenda.

The town in which I shot the project that I’m editing right now is in the middle of quite a poor area in rural Maine. While I was there they were restoring a huge sculpture that the town’s chamber of commerce built in the 1960s. It’s an 80-some-foot wooden sculpture of a Native American that they refer to as “the tallest Indian in the world.” Doing some research I found out that the town’s original name had been changed to a Native American name and, years later, they had built the statue in an effort to attract tourism. And I also found out that some of the worst genocides of Native Americans in the U.S. took place precisely in that part of the country, New England. So anyway, it was like, okay, why this big statue of a Native American? Are there any Native Americans around? It turns out, no, there are zero living in Skowhegan. I know it is common practice in the U.S. to appropriate and exotisize Native American cultures and that this practice has been normalized to the point that hardly anyone sees it, but to me, coming from the outside, it’s pretty crazy. I mean, it’s as if the Nazis had won the war and then decided to use a rabbi as a mascot for a city in Germany without any acknowledgment of the genocide, you know?

So they renamed it because it sounded Indian?

Exactly.

And what does Skowhegan mean?

It means a place to watch for fish. Crossing Skowhegan is a huge river called the Kennebec River where the Native Americans used to fish. For my piece I asked the members of the town’s committee in charge of the restoration to speak at a panel discussion at the local TV station about the history of the sculpture and about the use of Native Americans as symbols of the town’s identity. With my direction, the panel discussion slowly metamorphosed into a weird freestyle “Native American trance ceremony” that took place all around the TV station. This second part I left very much open to their interpretation. So yeah, that’s pretty much what I’m editing right now. The final piece will be a three-channel installation.

Sounds really amazing. How long were you there?

I was there for nine weeks. It was great because I was teaching but also had time to do the research and shoot during my last week.

Sounds really fantastic. So that’s what you’re working on right now—you’re editing the piece?

I’m editing that piece and I am also preparing for a solo show this November at Kake Gallery in Okayama, Japan. And soon I will start a new production for an exhibition at a space called HOME in Manchester, England that is being produced by them. Oh and finally I am working with the Phoenix Art Museum in Arizona.

Are you working with Julio César Morales?

Yes, with Julio.

“Mayonnaise” is what I call Julio. A slippery one. Oh man. So when is the show in Arizona?

Well, I’ve always wanted to do a piece about the Minutemen in Arizona. When Julio started working there he asked about the possibility of working together and I told him about the Minutemen idea. It took a bit over a year, but finally he set me up interviews with people around the state. So we’re going to do it in three stages. First is the field research this November, then production, and finally the exhibi- tion for which we haven’t set a date yet.

Beautiful. I don’t mean to shift a little bit here, but what is your take on how Mexico City fits within the contemporary art world, also considering art fairs like Zona Maco? You talked a little bit about the ‘60s, ‘70s, and into the ‘80s, and then the ‘90s with La Panadería, and now you mention a little bit about how things have shifted, but where do you place it today and how do you see it?

I think that the art world here is highly globalized. Mexico incorporated itself into the international art circuit and, like in most other places, there are increasingly more players coming from non-cultural sectors like business and finance. So that means that the art scene has grown a lot but that overall the emphasis has been shifting towards spectacle and profit and away from culture. Zona Maco is a good example of that. But at the same time the art scene is complex and there are many other forces at play that operate with a different logic. There are many great public museums and galleries in town, there is an international art symposium once a year (SITAC), new publications, and a very big population of artists that are increasingly opening up spaces and doing projects. So the scene in Mexico City is quite complex.

How would you describe the word “spectacle”?

Spectacle meaning it’s all about surface.

So they’re big shiny objects?

Big shiny objects or events that are more about corporate agendas or millionaires speculating on the market than about any kind of content.

When you say on an international/global level, are artists from outside coming in and exhibiting, or is it mainly a Mexican artist scene?

No, it means that art scenes in cultural centers like Mexico City can no longer be understood within a nation-state paradigm. Artists in the museums or galleries can be from anywhere, as can curators, collectors, etc. It is very international.

So today, La Panadería would be lost—if we go back in time and say you want to do an artist-run space in Mexico City today, would that be impossible?

Well, that’s SOMA. In many ways SOMA is La Panadería reinvented and adapted to this very different cultural paradigm that I just described. SOMA attempts to be a counterbalance by placing the emphasis on content and discourse, and by empowering artists so that we can exercise our agency. For instance, if there is an interesting exhibition in town, we invite the artist to give a talk at SOMA and talk in depth about the work. SOMA is a platform where conversations can take place and where issues addressed by artists can reverberate.

Exactly. And what is the makeup of your students? Are they all Mexican or do they come from everywhere? Actually, everywhere. That’s something that we did plan for the summer program in English but not for the two-year program in Spanish. But it turns out there is an international demand for what SOMA is offering because we have students from Colombia, France, Spain, Italy, Brazil, the U.S., and also students from all around Mexico.

There’s one thing that I want to—I don’t know if you want to talk about it or not, but I still remember when I was going to do an exhibition at La Panadería, and you got kidnapped.

And people thought it was you.

Everybody blamed it on me. I still remember when Carlo McCormick called me and said, “Dude, you’ve already done this, why do you keep doing this piece again?” And I tried to convince him, I did not do it! I think that was the best piece that I’ve done. I’ll take full credit for that. Well, Yoshua, it’s been a real pleasure.

![Pulpo [Octopus], 2011. Video still. Courtesy of the artist.](http://dfaq.mx/wp-content/uploads/2014/11/Screen-Shot-2014-11-17-at-10.51.22-1024x668.png)